Chris Hayhurst | Ed Tech Magazine

Colleges elevate active learning with major building and technology investments.

Assistant Director of Academic Facilities Hilary Gossett (Left) says collaboration was key to the design of the Edward St. John Learning and Teaching Center at the University of Maryland, College Park.

A new building at the University of Maryland, College Park has students and faculty alike turning their heads.

The Edward St. John Learning and Teaching Center, set like a jewel at the heart of campus, is a stunning work of brick and marble from the outside, with an array of windows reflecting the sky.

But it’s the building’s interior that’s really grabbing attention. The ESJ, as it’s often referred to, is UMD’s first facility dedicated to active learning.

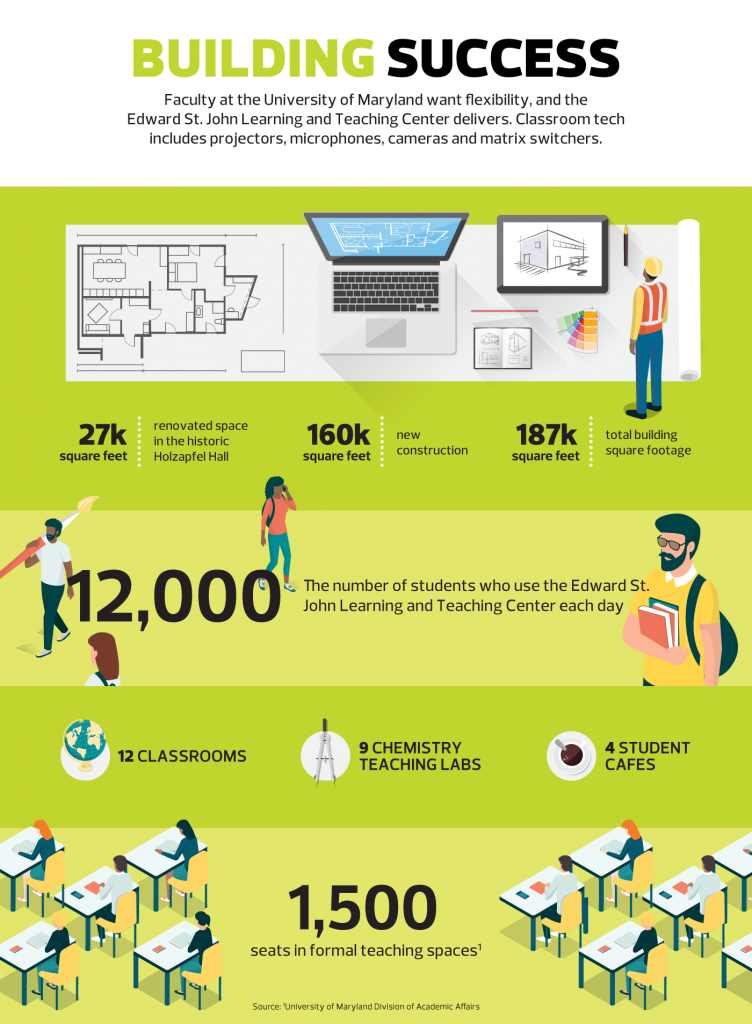

The $120 million building, opened in mid-2017, has 12 classrooms, nine chemistry teaching labs and four cafes across 187,000 square feet. It’s a place where students attend class and spend the day, and where the philosophy of active learning is evident throughout.

“The entire building was designed to support problem-based and team-based learning,” says Hilary Gossett, UMD’s assistant director of academic facilities. “It was imagined as a model of cutting-edge best practices — a building that would invite collaboration and creativity in new and unconventional ways.”

University of Maryland Sets the Stage for Classroom Engagement

The ESJ features four distinct types of active-learning classrooms intermingled with a variety of informal spaces.

“We call the classrooms TERPs,” Gossett says. That stands for Teach, Engage, Respond and Participate, but it also works out nicely that “Terp” is the nickname for students at the university, as well as for the Maryland Terrapins sports teams. The idea is that the design of the space invites everyone to get involved in each of those ways.

One style of TERP, the tiered-collaborative classroom, has fixed seating and rows of tables on tiers. Each tier is two rows wide, so students in the front row can pivot to face students behind them. The 6Round rooms feature round tables with six seats each, whiteboards and projection screens on surrounding walls, and a teacher’s station in the center.

Eye2Eye classrooms (the first will open this summer) feature lightweight, mobile desks that students can roll to wherever the conversation requires them to go. And, finally, there’s the media-share TERP, where peninsula-shaped tables jut out from the room’s perimeter and are outfitted with shared computers and screens.

“The rooms were all created in response to surveys we put out to our instructors,” Gossett says. “The main thing everyone wanted was flexibility: flexibility in how they and their students would interact with the physical classroom environment, and flexibility around their use of technology to teach.”

A variety of informal learning spaces, she adds, has made the building one of the most popular spots on campus.

Active Learning Classrooms Inspire New Ways of Thinking

It’s hard to find a university today that doesn’t have a modern classroom somewhere on campus. Less common, however, are institutions such as UMD that have invested in entire buildings with active learning at their core.

“That active-learning classrooms are catching on in higher ed really isn’t a surprise,” says Eric Kunnen, associate director of e-learning and emerging technologies at Michigan’s Grand Valley State University. “To me, though, the next step is going to be when universities start designing buildings to be collaborative from the ground up.”

He believes that, eventually, these environments will be critical not only to attracting students, but also to facilitating students’ success.

“When you build a space devoted to active learning that infuses technology and deliberately encourages collaboration and exploration, you’re creating a kind of academic beacon on a hill,” Kunnen says. “You’re telling students and faculty to think differently about what’s possible, and that this physical facility is there to support them.”

That idea was central to the construction of the $67 million Anteater Learning Pavilion at the University of California, Irvine completed in late 2018. The 65,000-square-foot space came about after UCI leaders reviewed research on the academic benefits of active learning.

“We’re a university that prides itself on the fact that half of our students are the first in their families to go to college,” says Michael Dennin, UCI’s vice provost of teaching and learning. “If you look at the evidence, you see that learning improves for anyone participating in an active-learning environment, but it especially improves for those first-generation students.”

Modern Learning Facilities Serve College Students Across Disciplines

Another reason UCI’s project got the green light, says Dennin, was “the big realization that building this pavilion wouldn’t have a negative impact on space for more traditional types of teaching. It would just add value to the campus as a whole and provide a place where faculty who were ready for active learning could thrive in classrooms designed for that purpose.”

The Anteater, Dennin notes, serves students from across the UCI campus, including those in liberal arts disciplines such as dance and history.

The Anteater, Dennin notes, serves students from across the UCI campus, including those in liberal arts disciplines such as dance and history.

“We have people from every discipline, not just the STEM fields, who are using the building,” Dennin says. “I think that’s a sign of how successful it’s going to be.”

The building includes a first-floor lobby and lounge, an assortment of labs and meeting rooms, and more than a dozen smart classrooms and auditoriums. Large classrooms feature shared displays and laptops at tables for six, while smaller spaces use movable chairs that let students swivel between groups and discussions.

Among the technologies in place are 27 Sony and Epson laser projectors, more than 75 flat-panel LGdisplays and 65 Dell Precision 3520 mobile workstation student laptops.

Critical to all of these tools, and to maximizing the learning experience, is switching, Dennin says. In most of the rooms, students work in groups at pods. They each need a screen for independent work, but they also need the ability to connect to a master screen and to see other groups’ screens.

Students accomplish these goals with Extron controllers, switchers and touch panels, says Dennin, and with nearly 100 Cisco Aironet 3800 Series wireless access points that serve as the backbone of the building’s wireless infrastructure.

While some universities have built active-learning centers from scratch, others, like Providence College in Rhode Island, find it makes more sense to add on to existing facilities. (UMD, in fact, also incorporated an existing historic building, Holzapfel Hall, into its new learning center.)

“For us, a combination of renovation and new construction made the most sense physically and financially,” says Charles Haberle, Providence’s assistant vice president of academic and technology facilities planning.

The college’s recently finished Science Complex features 35,000 square feet of new classroom, office and laboratory space, with another 80,000 square feet of renovated space in progress.

“We have active-learning classrooms elsewhere on campus, but nothing that is science-specific,” Haberle says. “This addition gave us the opportunity to do something innovative that would benefit our science faculty and students.”

Providence College Sees Big Results in Active Learning Spaces

Much like the new buildings at UCI and UMD, Providence’s complex includes double-rowed tiered seating in its light-filled lecture hall, chemistry labs with whiteboard projector screens and a common room where students can collaborate using their own devices or flat-screen monitors on the walls. Three classrooms feature movable tables and seats, equipped with everything instructors need to keep students on their toes, including carts stacked with iPad Pro devices and Apple Pencils.

“The key to active learning is flexibility and being untethered from a podium,” Haberle says. “When you put faculty and students in a setting that allows this to happen, you see incredible results.”

Because everyone is required to take science courses as part of Providence’s core curriculum, students from all over the college use the building. “They’re excited about the technology and the hands-on environment, and they’re eager to learn in a different way,” Haberle says.

Terp Tech: UMD’s Take on Modern Classrooms

The University of Maryland’s Edward St. John Learning and Teaching Center employs a wide range of active learning technologies, says Francis Bass, manager of classroom technology design. Among them:

- Switching: Crestron DigitalMedia matrix switchers (DM-MD8x8, DM-MD16X16 or DM-MD32x32) handle video switching and control signals. The Crestron DigitalMedia platform facilitates routing to Epson projectors.

- Projectors: Five larger classrooms use the Epson L1500U laser video projector, on ceiling lifts for easier servicing, and the remainder use Epson G7500U three-chip LCD projectors. Classrooms have two to four projectors, based on room type and size.

- Microphones: Every classroom has Shure ULX-D series handheld and lapel wireless microphones. Two large, tiered classrooms have two of each, as well as microphone (XLR) connections in recessed floor boxes at the front of the room to accommodate panel discussions. Catchbox throwable wireless microphones with a custom UMD logo are available in all classrooms.

- Cameras: Each room has at least two Vaddio RoboSHOT HD cameras. Large, tiered classrooms have four cameras that can be controlled within the rooms or from a separate master control room.